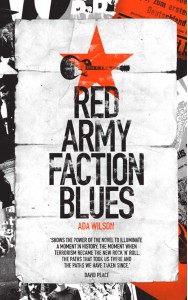

Red Army Faction Blues

'As a novel that is willing to both engage with radical politics and explore postmodern literary form, Red Army Faction Blues is a highly commendable work, audaciously conceived and well executed.' - The Review of Contemporary Fiction

Read More