Holy Cross Church was built by a team of volunteers using stone gathered from the ruins of Fryston Hall. It is the centrepiece of David Waddington's two volume history of the village, Pit-folk and Peers. The following extract tells the story of how the chuch came to be built. The principal characters in the story are Reverand John Daly and Jim Bullock.

John Daly was born in Surrey and educated at Cambridge. He spent a year at Cuddesdon Theological College (Oxford) and was ordained at Durham Cathedral in 1926 before agreeing to become a curate at St Mary’s in the slum parish of Tyne Dock. Conditions there were similar to what he’d later find in Fryston. ‘The first person I buried was a coal miner. He died of starvation at the end of 1926. It was the General Strike,’ he recalled in 1986. Three years after arriving on Tyneside, Daly was summoned by his old College Principal, Jimmy Seaton, who was by now the Bishop of Wakefield. He explained that he wanted Daly to set up a new parish in and around Airedale in the Yorkshire Coalfield and build a new church. An ecclesiastic district could not become a parish until it had a church large enough for a congregation of 500. The new priest was greeted on his arrival by the intimidating presence of ‘a large roughly hewn wooden cross’, marking the designated location for a permanent church building to replace the existing temporary construction. Local people had raised £300 towards the building of a new church.

Daly was a personal friend – and ex-colleague while he worked in London – of the Reverend Philip (‘Tubby’) Clayton, who was the founder of Toc H, an institution dedicated to applying the skills and expertise of male volunteers to the needs of their neighbourhood and community. Daly took the decision, shortly after arriving, to form an Airedale branch of Toc H. Jim Bullock was among the dozens of local colliery workers who immediately enlisted.

Jim Bullock was from a coal mining family who had quickly risen from collier to Undermanager of Fryston Pit by the age of 28. He had previously lost a brother in an underground accident and was thus determined to improving the safety and living standards for the pit-folk of Fryston. He’d recently rigged a ballot of the miners to ensure they voted in favour of building a modern pithead baths at the colliery. He could see the benefits of it yet was also aware of the scepticism of colliers who superstitiously worried that washing the coal muck off their backs might sap them of their strength. So Bullock had the the 'no' votes switched to 'yes' and a state-of-the-art baths was built. When Bullock later became manager of the pit, he pioneered many initiatives for the welfare of his workforce, all of which are outlined in Volume 2 of Pit-folk and Peers.

Fryston Hall was the 19th century home of the poet, politician, biographer and philanthropist, Richard Monkton Milnes, the first Lord Houghton, principal character in Volume 1 of Pit-folk and Peers. It was also the childhood home of his son, Lord Crewe, the principal peer in Volume 2, who returns to the village to lay the altar stone at Holy Cross Church, as recounted in this extract.

Rolling Away the Stone

John Daly had been shrewd enough to realise that the sum raised by local people of £300 was insufficient to finance the building of a church. In casting around for a cheap source of stone, he came across a disused church on the corner of the ‘Shambles’ in York’s city centre, but the Archbishop denied him permission to use it. Then fate appeared to take a hand. One day when he was being given a tour of Fryston Woods by a local Rover Scout, they came across ‘a large, derelict manor house’, comprising the remains of Fryston Hall.

I was immediately interested because the stone looked good and we’d obviously got to get some stone if we wanted to build a church. So, I reported it to the Bishop and, a few weeks later, he said, ‘You can have it for £300,’ which was exactly the amount of money we had managed to raise. Having blown the whole of our £300, we still needed someone to pull the building down. (John Daly, 1986)

Once the purchase had been approved by the Bishop’s nominated architect (Sir Charles Nicholson), Daly set about dismantling the building in such a way as to preserve the magnificent pillars (porticos) forming the entrance to the hall. On Easter Monday, 1931, local worshippers conducted a short service in the old Ballroom at Fryston Hall, seeking Divine Blessing for the stone, and those responsible for its deconstruction and removal. Jim Bullock maintains that Daly turned to him to see that the job got done: ‘He came down to see me and I took a team of men with blasting material from the pit and blew the whole place up, but we protected the pillars.’

The manager of nearby Glasshoughton Colliery (a Mr Elliott) agreed to provide an old T-Ford Truck, capable of carrying the stone up the hill to Airedale. He also paid for the petrol and driver’s wages. When it became necessary for the latter to resume working down the mine, John Daly personally took over the driving:

They were big, big pieces of stone, but we tried to move them without chipping them. Some of them were approaching two tons and we only had a one-ton truck. On one occasion, we were going along with certainly more than one ton on the back and the front wheels came off the ground and our load slid onto the floor! These types of thing tended to happen, but we were generally ok because we took our time. We used over 600 tons of stone, but we also needed to put in 400 tons of reinforced concrete because, as they explained, the church needed to be built on a ‘raft’ as the coal had been taken away underneath. For this we needed broken brick. Again, Mr Elliott sent me a chit saying they were going to lower a 100ft chimney and we could take what we wanted as long as we looked sharp about it. (John Daly, 1986)

Once again, Jim Bullock volunteered his services and those of other colleagues. It was Bullock who also provided a brick-crushing machine. Each morning, after mass, but before breakfast, Daly would drive off to collect a ton of bricks from Glasshoughton, before depositing them at Fryston to be broken up for the foundations. There were no limits, Jim Bullock maintained, to Father Daly’s resourcefulness:

The vicar went round all the pits and building yards begging old girders, borrowing cement mixers and lorries. I understand he even sacrificed six months of his own salary in advance to pay for materials we needed – a truly wonderful character – he really did know how to get the best out of people.

‘The Church’s One Foundation’

Bullock also recollected how John Daly had turned up at a Toc H meeting and requested that local miners engage in the digging out of the foundations for the new project. The first sod was dug out by Oscar Fisher in February 1932, after which local women and children all pitched in with commendable enthusiasm. Bullock duly arranged for teams of Fryston miners to work on successive shifts. One such group (of cement mixers) consisted of six of the ‘roughest’ and ‘strongest’ men in the pit. Fortunately, as Bullock explained, ‘John Daly didn’t mind my miners swearing, what he wanted was to get some work out of them – and he did.’ Once the foundations had been laid, an invitation was despatched to Lord Crewe, asking if he would do local people the honour of laying the altar stone.

‘Stone By Stone, A Hall Becomes A Church’ was the headline accompanying the report by the Pontefract and Castleford Express (24 March 1933) on the events of the previous Saturday, when Lord Crewe obligingly laid the altar stone, as requested. This Holy Cross Church was being built, of course, from materials emanating from his former ancestral home. It was, as the Express put it, ‘a day of reminiscences’, adding that many of those in the audience could ‘remember the old days at Fryston Hall, the Christmas parties and the Bible classes held there’.

The laying of the stone was preceded by a short service. Aside from Lord Crewe, the ceremony was attended by: the Bishops of Wakefield and Pontefract; officials of Airedale Collieries; the Mayor and Mayoress of Pontefract; and companies of Girl Guides and Boy Scouts. Following the singing of the hymn, ‘The Church’s One Foundation’ (set to music provided by the St John’s Ambulance Brigade) and the offering of prayers, the altar stone was blessed by the Bishop of Wakefield. The Bishop marvelled that the stone, which had been extracted from Fryston Colliery’s Beeston Seam, was in the region of 500 million years old.

Lord Crewe was presented with a mallet, which he then used to lay the stone, ‘in the faith of Jesus Christ our Lord […] that here true worship may for ever be offered, and true faith, with brotherly love, may for ever flourish and abound’. He commenced his speech by casting his mind back, some 60 years ago, when his parents lived at Fryston Hall and he had the pleasure of cutting the first sod for the new Fryston Colliery. In turning to the present day, he glowingly observed that:

Nothing was more striking or admirable than the way in which the people of Airedale had interested themselves in the scheme for the new church and had worked very hard for its erection. The church, when complete, would be an enduring monument of what could be done by the efforts of the many. The times had gone when churches could be built through the generosity of individuals, but the Airedale Church would be no less worthy and no less holy because it represented numbers rather than individuals. Times had changed from the days when the valley of the Aire was one long stretch of smiling country, and salmon could be caught in the river. Those days seemed almost as remote as the days of Oliver Cromwell and the Battle of Marston Moor. One thing had not changed, however, and that was the spiritual need of mankind. It was to satisfy those needs that the church was to be built, and he hoped to fulfil its purposes.

In thanking his lordship, the Bishop of Wakefield declared that this was a singularly happy occasion. ‘Nothing could be more fitting,’ he confidently stated, ‘than that stones so rich in English literature should be preserved and sanctified, and become the spiritual home of the people.’ The Bishop applauded the ordinary people of Fryston and Airedale for all the hard work and financial generosity they had committed to this project, and heartily complimented the Reverend Daly for the ‘inspiring leadership’ he had exhibited. The Bishop thought it ‘fitting’ that the altar stone should have been excavated from Fryston Colliery: ‘It was perhaps millions of years old, and would remind them of the One Eternal Father. The name “Holy Cross” spoke of sacrifice, and the building was being erected by the sacrifice of working people in very hard times.’ Then, once the ceremony was over,

Lord Crewe was surrounded by residents, and appeared to enjoy his chats with the old people. He also joined the company who took tea in the Airedale Council School, and again chatted freely of former days. He left to the accompaniment of hearty cheers.

Mission Accomplished

The completion of the project proved even more arduous than anticipated. It had first been necessary to strengthen the foundations by employing countless yards of steel rods to offset the risk of subsidence posed by underlying worked-out coal seams. Daly had set on an unemployed former bricklayer, George Westerman, to perform and oversee the actual building of the church. Since October 1932, four further workers (a combination of stone masons and site labourers) had been signed up to hasten the completion of the foundations and assist in the stone and brick work. One day, as Daly explained,

George told me that the wall was getting too high for them to lift the stone and proposed that I should ask my sister to donate the front wheel of her bicycle; it was with that, as a pulley wheel, that the whole church was built. Many minor miracles accompanied the building: we were never overdrawn at the bank; a firm saved us hundreds of pounds by lending us tubular scaffolding on the understanding that we could return it to their warehouse within two weeks of their recall; they recalled it two years later, ten days before we had completed the work. When all was done, we found that there was just enough stone left to build a surrounding wall. No one was hurt and we never had a strike!

The Holy Cross Church was finally consecrated on 14 July 1934. With the project now completed, Daly received a call, one year later, from the Bishop of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), inviting him to become one of his mission priests. Excited by the prospect of a new challenge, Daly wrote to the Bishop of Wakefield, seeking his permission to leave Airedale.

He surprised me by replying that he did not think that I should, but that I must go to see him in a fortnight’s time. Meanwhile coming home one very cold morning from the Daily Eucharist in our new church I saw a pile of letters on the breakfast table. My sister remarked, ‘There is an envelope there marked Lambeth Palace, I expect the Archbishop wants to make you a Bishop!’ and we both laughed. The letter had been written by the Archbishop’s Senior Chaplain, who had been my theological college chaplain. It started ‘Dear John, I’m afraid that I am going to put a bomb under your chair.’ He continued that I was summoned to London to see the Archbishop who was considering me as the first bishop of a new diocese in West Africa. And so it was that in 1935 I was consecrated and sent to the Gambia with my first Mitre.

Daly’s consecration as Bishop of Gambia and the Rio Pongos, at the age of 32, made him the youngest person in the Anglican Communion ever to achieve that status. He subsequently became Bishop of Accra in 1951 and of Korea in 1955, and the first-ever Bishop of Taejon in 1965. A heart-warming acknowledgement of the fabulous legacy bequeathed by Daly to the residents of Fryston, Townville and Airedale was subsequently proffered by his old friend, Jim Bullock, who wrote:

John Daly has gone to a much bigger job – he is now a bishop – but as long as ever Holy Cross church in Airedale stands it will be a testimony to John Daly, for without his vision and his drive it would never have been built. It is also a testimony to hundreds of miners, to some colliery managers and to many other people who did what they could to help him in this wonderful project. Wherever John Daly is I am sure he will never forget the days he spent at Airedale or the friends he made while he was there.

Image: Most of the relevant spadework was undertaken by local volunteers, including the wives and children of Fryston and Airedale miners.

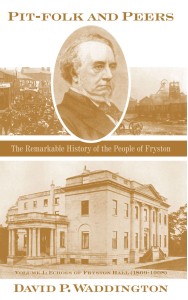

Read more from Pit-folk and Peers: The Remarkable History of the People of Fryston Volume 1 (1809-1908) and Volume 2 (1909-2023). The two book covers reveal how Holy Cross Church is a pivotal point of the story. Fryston Hall features on the front cover of Volume 1, and Holy Cross Church features on the front cover of Volume 2. You can see the stone pillars connect both buildings.