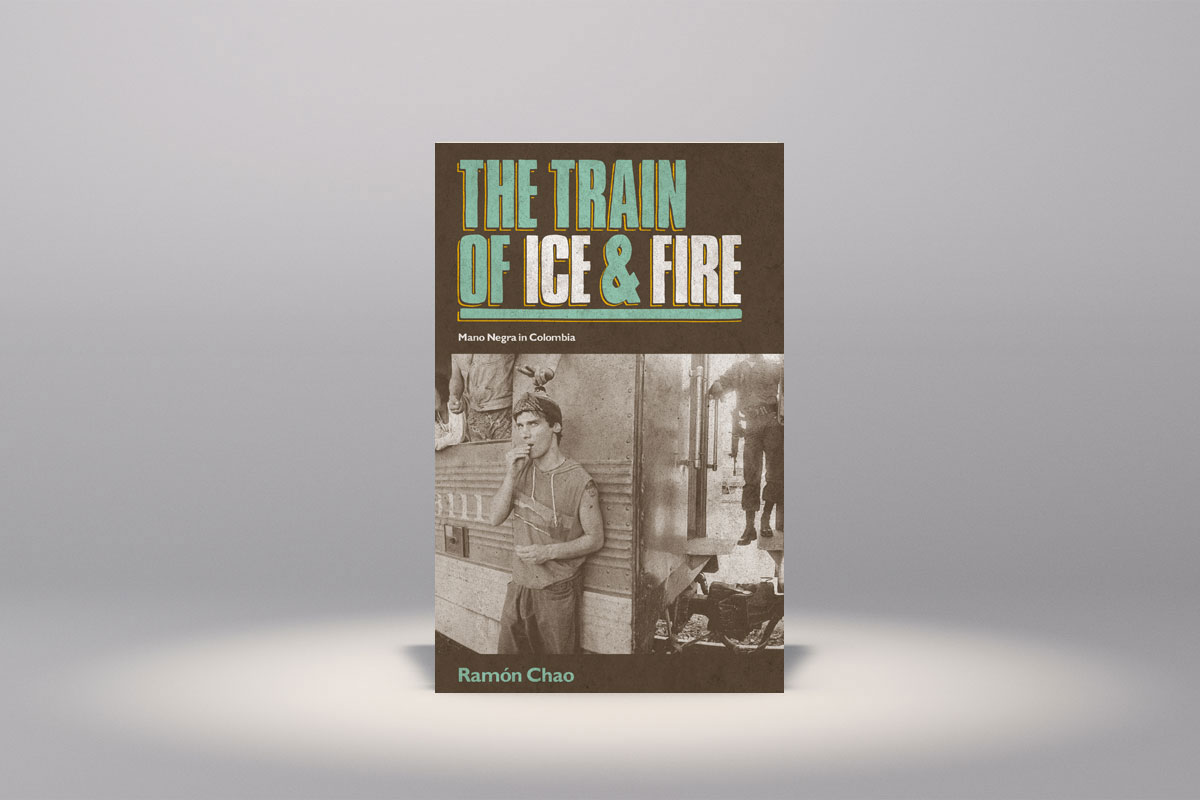

Ramón Chao's prologue to The Train of Ice and Fire

I went to Colombia because I was scared. My two sons were involved in a journey on an as yet non-existent train, on rusty tracks, through dodgy guerrilla country. They would be crossing the Bajo Magdalena – the lower reaches of the Magdalena river – one of the most dangerous places on earth, an insurgent stronghold, fought over by paramilitaries, drug traffickers, criminals, kidnappers, murderers, or possibly all of them rolled into one. I was scared for them. Antoine went to Colombia first, to prepare the infrastructure for the trip, and stayed several months. He returned to Paris to attend to more pressing projects, and Manu left for Colombia with most of his rock group Mano Negra.

The previous year, on the group’s Latin America tour (part of the Cargo ’92 enterprise), Manu had noticed there weren’t any railways in Colombia. True, there were grass and moss covered tracks and deserted railway stations, but the omnipotent air and road monopolies had gradually seen off the more democratic railways. Manu, who is very stubborn, was determined to reactivate a form of transport that is so crucial to a country’s social and geographic fabric. Their train would go from Bogotá to Santa Marta and back, stopping at ten stations to give rock concerts, circus and theatre performances, and an exhibition of ice sculptures.

I repeat, I was scared. There was talk of kidnapping, hostage-taking, murders. Manu was over there in the thick of it and I was in Paris calmly (so to speak) going to exhibitions, plays and libraries. I caught the train literally as it was moving off, under the illusion that with me beside him nothing could happen to Manu. But lots of things did happen. Firstly, the resurgence of our family’s Hispano-American past. Watching my son dancing salsa convinced me that something from over there was in our genes. At home I’m considered a bit of fantasist, but my sons’ attachment to the people and music of Latin America confirms my suspicions: my paternal grandfather is not the one that figures in our family tree, but Mario García Kohly, minister in the government of Cuba’s first president Tomás Estrada Palma, and later Cuban ambassador to Spain. My grandmother left Galicia for Cuba, fleeing her quarrelsome drunken husband. She worked as a maid in García Kohly’s house and got involved with him.

García Kohly’s house was a meeting place for musicians and writers. The host himself wrote poems that didn’t make much of a mark, except for the words of the habanera ‘Tú’ that he wrote under the pseudonym Ferrán Sánchez. The composer Sánchez de Fuentes was a regular visitor to the house, and it was he who put the habanera to music. I deduce from all this that the ‘Tú’ in question, symbol of Cuban sensuality, was that beautiful warm Galician lady with blue eyes and rosy cheeks; my sons’ great-grandmother.

‘In Cuba, beautiful island of burning sun,

under its sky of blue,

adorable brunette,

of all the flowers,

the queen is you.’

The drunken husband who had stayed in Galicia, arrived in Havana one unfortunate day looking for his wife. And since the droit de seigneur (the right to a legover) brings with it the duty of protection, the man was found with a bullet in his head at the corner of Escobar and Galiano, in Old Havana. I imagine that in Cuba it wasn’t difficult for anyone with influence to order whatever he wanted. My father was born shortly afterwards. His strong likeness to García Kohly, according to a photo of the former ambassador in the Spanish encyclopaedia, leaves my detective thesis in no doubt. I don’t want to cast aspersions, but astral calculations indicate that my father was conceived after my grandmother fled Spain and before the arrival of her wretched husband.

García Lorca said that to be a good Spaniard you have to have a Latin American dimension. My sons had discovered that in Paris. Apart from the fact that my professional activities involved Latin America, at home we always played the music of Beny Moré, Violeta Parra, Atahualpa Yupanqui and many others. Bola de Nieve’s song ‘Ay Mama Inés’ that Manu included in his repertoire, was one that he heard and sang all the time as a child. Manu reminded me not long ago that as teenagers, he and Antoine got into all sorts of mischief, but when they came home they’d meet someone like García Márquez, and that redressed the balance. I remember one of the first things Manu played on the guitar was a piece by the Cuban musician Leo Brouwer, and the first percussion instruments he and Antoine had were brought from Havana by Alejo Carpentier. For his part, Antoine was musical director of Radio Latina in Paris for a time and now produces Cuban music records, keeping close ties with the island.

In this book, I recount the vicissitudes of the journey made by the Train of Ice and Fire. They called it that because it was pulling a flaming wagon full of huge blocks of ice to Aracataca, Gabriel García Márquez’ home town. Remember the opening chapter of One Hundred Years of Solitude when the gypsy Melquíades brings ice to the children of Macondo for the first time? But I think the most important thing, the thing that affected me most emotionally (apart from the wish lists the Colombian kids wrote) was the break-up of Mano Negra, that mythical group created by Manu, and including Antoine and my nephew Santi, that began rehearsing in the basement of my house.

Manu saw the train through till the end, but was totally burnt out. In another book, I recount how he recharged his batteries on a pioneering journey by motorbike from Paris to Compostela, passing through places where the martyred bishop Prisciliano (executed in Tréveris and buried in Compostela in a tomb arbitrarily attributed to Santiago) had preached. To face a new life as a solo artist, without his band, Manu gathered strength from the land and sea of Cape Finisterre, where Old Europe ends and you look out towards the New World. In the bars of Camelle and Muxía, he began to write ‘Bixo’, ‘La Vaca Loca’, ‘La Despedida’…and the rest is history.